ICE’s Acting Director recently announced his vision of a removal machine that works like “Amazon Prime but for human beings”.

When your Amazon package doesn’t arrive because it’s lost in transit, someone compensates you and delivers another. But human beings are irreplaceable to the people who love them. So when you lose a human being in transit, the Amazon model doesn’t work. The person is gone, and can never arrive at the destination.

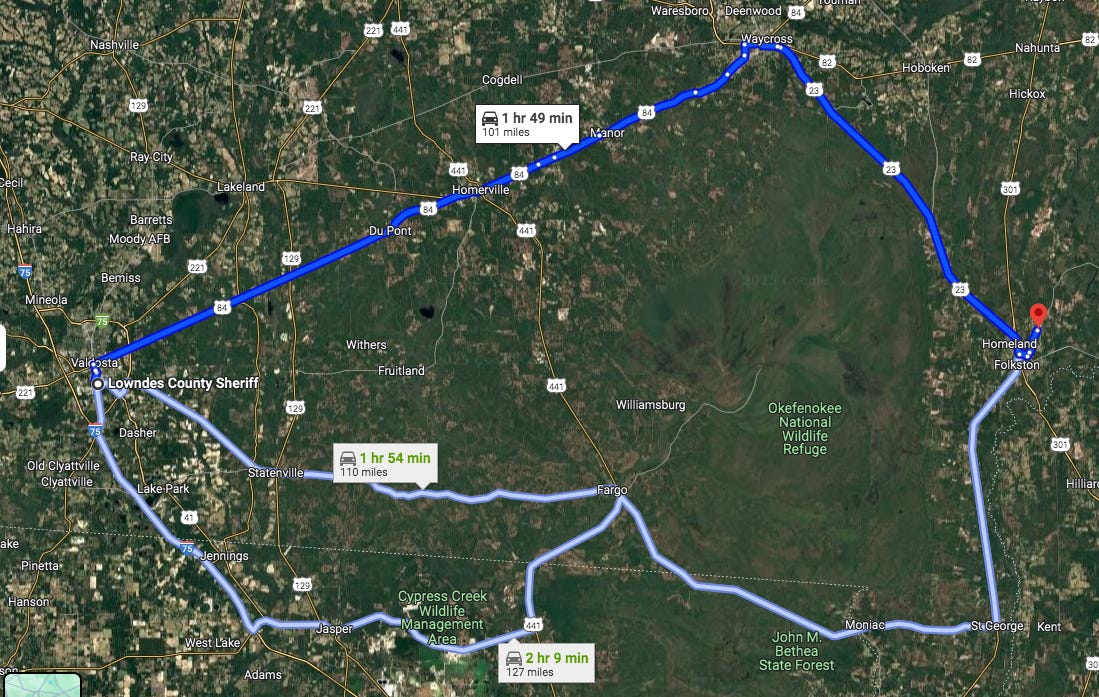

Predictably (and tragically) that’s exactly what happened last week. 68 year-old Abelardo Avellenada Delgado reportedly died in transit while CoreCivic subsidiary Transcor was moving him from the Lowndes County Jail in Valdosta, Georgia to the Stewart County Detention Center in Lumpkin. He got as far as Webster County, where the coroner received his remains. The 132-mile trip proved too much.

The pathway implied by ICE’s account of this death in custody highlights one of the most opaque and infuriating aspects of the deportation machine — one that no self-respecting just-in-time Amazon logistician would stomach, because it’s so obviously inefficient and based on profiteering and protectionism.

The highway to this man’s death traveled northward, to a for-profit prison 150 miles away. But the nearest place to accomplish the delivery of this human cargo to a detention center wasn’t that far. It was at Folkston, just through the Okefenokee Swamp, only 101 miles way:

So, why the inefficiency, which interrupted this man’s immediate access to emergency medical care in a facility medical wing?

The answer could lie in the structure of ICE’s for-profit detention contracts. Or, more specifically, in parts of those contracts where the companies stake out claims to transport people from various local jails and ICE sub-offices on regular routes in exchange for cash. Here’s what this looked like for GEO and ICE at the Moshannon Valley facility, according to a public records request response:

The ICE contract thus sets the carceral geography by allocating transportation dollars to the prison profiteer, and incentivizing that company to grab these resources.

Another aspect of the contracts that may have dictated this particular man’s site of detention are ICE’s guaranteed bed minimums. A guaranteed minimum bed clause in an ICE detention contract basically pays the contractor to maintain staffing for a minimum number of humans, and then pays an extra amount per person per day if the population exceeds the bed minimum.

The Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General repeatedly criticized ICE’s expenditure of finite government resources on facilities that didn’t meet these minimums. The watchdog “calculated that ICE paid approximately $160 million for unused bed space under guaranteed minimum contracts,” according to a September 2024 report.

ICE itself penalized at least one contractor, CoreCivic, which operates Stewart, for using a single doctor to staff more than one of its New Mexico facilities. The same ICE Contract Discrepancy Report found “the actual medical staffing level is 44.92%, far less than the 95% staffing levels indicated in the response.”

The contractually guaranteed minimum is a combined 882 people detained per night for GEO’s Folkston Main and Folkston Annex facilities. It is 1600 for Stewart. One way to maximize marginal revenue is to ensure you run your vans (in GEO’s case, GTI, in CoreCivic’s case, Transcor) and fill them with the human beings you need to take advantage of every single additional per-person, per-day invoice charge.

There are, of course, even more ridiculous examples of ICE using transportation to far-flung detention facilities in order to defeat habeas jurisdiction, retaliate against people inside for organizing, or warehouse a certain type of would-be deportee in a place where they’ll be more easily disposable. Bluebonnet, Jena, Torrance, and Krome come to mind.

We don’t know how this man died, and ICE won’t say. We don’t know why ICE ERO Atlanta designated Stewart as his site of incarceration rather than Folkston. We’ll find that out eventually.

But it’s fair to assume that if Amazon customers paid extra to have their truck drive an hour out of the way because the company they bought their items from profited more, that wouldn’t be something the market would generally permit.