Community Resources for Documenting Deaths in DHS Custody - Part 2: Why You Should (Almost) Always Do A Second Autopsy

Stories from the field show why independent forensic analysis of people who die in custody is vital to uncovering the truth and seeking accountability.

“Andrew, someone hurt her,” said the forlorn voice on the other end of the line.

The tone our independent forensic pathologist used as he stepped out of the examination room to call me mid-autopsy was one I’d never heard before. His usual cheerful, breezy banter was gone. There was a gravity and urgency to it that grew out of his shock and revulsion at what he’d found. Gone was his ordinary mix of cold, fact-based post-mortem findings, followed by a kindly layperson’s spoonfed explanation for consumption by a novice like me, then softened with the anesthetizing gallows humor one develops over time when your job is to pick at dead bodies all day as your state’s chief medical examiner.

“Someone hurt her”

independent forensic pathologist, during a call mid-autopsy

“This isn’t from CPR,” he said. “It looks like someone took a baton or an asp and hit her on her sides and ribcage while she was handcuffed. There would be defense wounds for something like this. She has deep, severe subcutaneous bruising from the cuffs, like she was trying to defend herself, but couldn’t.”

The government denied pre-death physical abuse transgender by asylum-seeker Roxsana Hernandez’s jailers when we held a press conference sharing the findings of the second autopsy. But they also dead-named her and failed to ensure the for-profit prison they transported her to preserved the video that would reveal the truth. And they refused to invoke the Federal Records Act remedies, which include criminal prosecution, for unlawfully destroying the video, even when the Archivist of the United States demanded an explanation.

Instead, ICE’s PR flaks trashed our forensic pathologist’s reputation on background to the press—feeding supposedly damaging material about him that they said undermined his scientific conclusions. We know this because one brave journalist and their outlet refused to grant ICE its unilateral ‘for background’ agreement and published the mud the agency was slinging. Kate Sosin at Into showed journalists how reporters at the Washington Post and New York Times, among other outlets, were all too willing to uncritically parrot the government’s preferred talking points.

Another, highly qualified state forensic pathologist told me when I asked whether there was anything to the government’s mudslinging, and if I should be worried we’d been misinformed, that when you decide to do independent autopsies as an expert for anyone other than the State, you keep a letter of resignation in your desk drawer. You know that if you end up finding out too much truth the bosses will come for you and make it impossible to continue doing your work. Covering up wrongful deaths can be a dirty business whether you’re exposing the murderers on Danziger Bridge or calling out unexplained delays and indefensible conclusions in other offices’ work. Anyone willing to do it knows this. You can read more about this racist legacy and the public health emergency it’s created from two of the best in Jay Aronson and Roger Mitchell’s book, Death in Custody.

Critically, at least in my view, the pathologist’s scientific work was still good enough for the State of Georgia’s prosecutors to use it to convict and imprison people. He was never disqualified as an expert by any judge, and if it’s good enough for the prosecutors of the carceral state, it’s tough to understand why it wouldn’t be good enough for ICE. They just didn’t like what the independent autopsy had to say.

ICE and its contracted scientists at the University of New Mexico Office of Medical Investigator denied pre-death physical abuse without admitting they hadn’t actually performed the dissections, subcutaneous tissue inspection, and photography that our pathologist did. Even more important—nobody from the federal government ever asked to see the autopsy photographs that substantiated our pathologist’s findings before ICE denied they were true. They didn’t like the conclusions, so they attacked the messenger who reached them.

Reasonable scientists can and do disagree about autopsy findings. My point in sharing this story is that unless families and communities have someone analyzing the remains of a person who died in custody, the only side of the story that will ever be told is the government’s. And that’s unfortunate. Because, as we’ve spent years documenting, the government’s M.O. is to lie, omit, and obfuscate every time someone dies in custody—at least until they’re forced to own up to the truth of what really happened.

You find out a lot when you secure an independent autopsy. It gives you an opening to speak with the pathologist who conducted the first one and, ideally, to facilitate the transfer of records and lab results and findings from their office to the professional you’ve retained. This helps guide the fact investigation and can help orient people conducting it toward the questions that will help get to the truth.

For instance, if a person dies in ICE custody of what looks like a heart attack, but the toxicology results reveal there was a drug in their system that didn’t belong there, inside organizers and outside investigators can focus their post-death inquiries on the way that drug got into their bloodstream. We know from multiple death cases, most notably (for now—stay tuned) Gourgen Mirimanian’s, that even when confronted with toxicological evidence of a substance in the decedent’s body that shouldn’t have been there, the government’s investigators refuse to ask how it got there. This matters because the company that runs the facility where he died destroyed video with the best camera angle and, suspiciously, lost commissary records.

“If we autopsied everyone we find along the border, that’s all we’d be doing all day” - Border State Death Investigator, May 2018.

In another case, retaining an independent forensic pathologist revealed that the Justice of the Peace didn’t actually intend to conduct anything more than a “visual autopsy”. “Looks dead to me. No trauma. Sounds like they were unhealthy. No toxicology.”

Or, as the investigator I spoke with told me by phone when I informed him we’d be taking custody of the person’s remains and needed his help transferring him to a facility with an exam room and cold storage, “you have any idea how many bodies there are down here? If we autopsied everyone we find along the border, that’s all we’d be doing all day. These people don’t have families we can contact, and we didn’t ask them to come.” The shock of his words ripples through my soul even today.

If we hadn’t contracted someone to come in and dissect the person’s remains, the government would never have admitted he died of bacterial meningitis, something that put everyone in the places he was imprisoned at risk of illness, and something ICE failed to disclose. But once our guy got down into the hot Texas sun, the body was unavailable for him. The government had changed its mind, and decided to do an actual dissection, now that they knew someone would come to check on their work.

So, what stops us from obtaining independent autopsies every time a person dies in custody? In my (limited) experience, four main challenges prevent independent autopsies. The first is a combination of disconnection and fear. families and communities abroad are either disconnected with U.S.-based death investigation and accountability teams, or fearful of coming forward to access them, lest they themselves become targets. This is particularly true for those living without papers in the U.S. and for those living abroad on the run from persecution, war, or violence.

If we can clear this first hurdle before ICE disposes of the remains or they decompose past the point of being subject scientifically reliable collection— which is often no easy feat under current conditions — the second obstacle to securing an independent autopsy is resources.

Who will do it? More important, who will pay for it?

Colin Kaepernick should have been playing in Super Bowls, but because NFL owners wouldn’t allow that, he chose to put his money towards solving this problem instead.

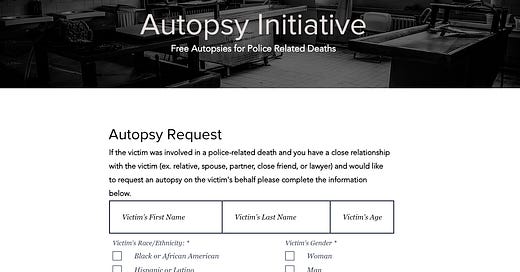

The Know Your Rights Camp Autopsy Initiative provides free, independent autopsies for people killed by police and those who die in jails. I learned about this from a presentation their team gave during the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab Deaths in Custody Conference in Austin, Texas last November. It’s my understanding that they’ve already paid for at least one independent autopsy of an in-custody ICE death. They have a request form on their website, and a host of amazing people on the back end working to fulfill this request.

Over the years, communities I supported raised more than $75,000 to facilitate independent autopsies. It was often done through ad hoc GoFundMes that wouldn’t pay out immediately. This required either a pathologist willing to do the autopsy on spec or a deep pocketed donor willing to float the autopsy fees until the GFM paid out to get reimbursed. KYR Camp’s Autopsy Initiative solved this second problem.

I have resolved to donate a meaningful amount to me to KYR Autopsy Initiative each time someone dies in ICE custody. I highly encourage you to consider doing the same, or sharing their donation link to allow others with the desire and means to do the same. Even if you can’t materially support this Initiative right now, just knowing about it will enable you to share it when it’s necessary, so even though I’ve posted about it before, I’m re-upping it here.

Donation link here.

The third hurdle we often run into once we have contact with family members and the necessary resources to identify and pay for an independent forensic pathologist is government recalcitrance in providing the records and information our doctors need. ICE has no formal, federal autopsy policy. It’s up to the state in which the person died, and in that respect, it’s also, to a certain extent, up to the ICE contractor tasked with complying with those state laws.

Doing this work in Georgia spoiled me. Every death in custody, I once believed, requires the Georgia Bureau of Investigation to come in and conduct a law enforcement investigation. These post-death engagements typically “start as homicide investigations,” a former death investigator told me, “and then work backwards until you’ve ruled that out.” That’s because you don’t know when you begin whether the person was murdered—either by another person in custody or a correctional officer—and until you’re sure, ignoring that possibility functionally allows the murdered off the hook.

I would point folks who think this is outlandish to the case of Roger Rayson, whose horrific 2017 death in GEO’s Jena, Louisiana facility was one in which the local authorities could not rule out homicide as a cause of death, according to ICE’s own records.

I was shocked to learn that places like New Mexico and California and Washington provide less effective means of checking against in-custody homicides and cover-ups than Georgia. I grew less shocked and more disillusioned when California governor Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill I helped advocates draft and pass that would have allowed the state’s DOJ to investigate all deaths in civil custody. Apparently the sheriffs didn’t want to be subject to that kind of heat.

I later learned Georgia isn’t exempt from that sort of lobbying. Fulton County Sheriff and former Atlanta City Detention Center corrections chief Pat Labat doesn’t want that kind of heat either. He’s somehow managed to exempt himself from these GBI investigations, instead handing the information over to local investigators. Not to stray too far afield from the migrant detention death focus, but I see no good reason why GBI shouldn’t go in and interview witnesses, pull video, subpoena records, and reach an investigative conclusion about deaths like this one, rather than the jailers investigating themselves.

So, assuming you’re able to get the requisite blood samples, medical records, and factual information preserved and delivered to an independent forensic pathologist, the fourth main stumbling block I’ve experienced comes from a visceral rejection by loved ones—sometimes rooted in religious beliefs or cultural traditions—to the idea that after caging and killing a loved one, we must now cut them open and empty out their organs. It’s really important to simply respect these sensitivities and not try to assign primacy of a particular investigative strategy over them.

There’s plenty of room, even without an independent autopsy, to review the original one and assess whether its methodology conclusions are scientifically sound. In other words, even where the family’s decision is to forego scientific investigation into their loved one’s remains, there’s room for forensic pathologists to apply their expertise to the records created by the state, and challenge the legitimacy of the state’s conclusions if that’s where the science leads.

A great example of this happening was the July 2020 Congressional hearing over the deaths of children in Border Patrol custody. Dr. Roger Mitchell, who helps advise the KYR Autopsy Initiative, testified before Congress that the conclusions of the government were unsupported by the science. CBP’s medical neglect, not the alleged neglect of the children’s parents, was what caused their death, according to the best evidence available. Maybe sometimes that’s the best we can do, even if it’s too little too late. Forensic pathology was critical to establishing these facts and correcting the historical record.

I think the bottom line here is this: Always get an independent autopsy (if you can and if it’s what the person’s loved ones want).