“Only the written word is law, and all persons are entitled to its benefit.” Bostock v. Clayton County, 590 U.S. 644 (2020) (Gorsuch, J.)

Most ICE arrests in the U.S. are unlawful, extra-statutory kidnappings. We can stop them by demanding the agency’s fulsome compliance with the law from federal judges.

Now that I (hopefully) have your attention, let’s back up and do some scaffolding so that we’re all able to get where we need to go together.

A defining aspect of the present regime’s approach to immigration law is its reliance on the text of obscure, arcane, and antiquated laws to instill fear, rationalize state violence, and amass purportedly unreviewable power. Whether it’s invoking the Alien Enemies Act (1798) or requiring noncitizen registration using the Smith Act (1940), further militarizing the U.S.-Mexico border using “Roosevelt Reservation” (1907) federal land rights to circumvent posse comitatus (1878), or invoking McCarthy-era Red Scare powers if the Secretary of State to cancel visas and revoke green cards (1952) for thought crimes, those currently in charge have proven adept at using the letter of law as a sword and a shield. Like ticking time bombs, the racist, nativist fears our forebears wrote into statute have become tools of terror for today’s authoritarian would-be despots.

By and large, it’s worked. At least until judges get involved and review their actions, with varying levels of haste and success.

In this piece, I share why I believe the letter of existing law, and the weight of current, textualist jurisprudence at the Supreme Court, can be used to immediately halt (at least temporarily) roughly 60-70% of ICE apprehensions in the U.S. Not because I don’t like them (I don’t). But because the law forbids them (it does).

I fully acknowledge mine is the heterodox view. But, I contend, that does not render it ispo facto incorrect. Many modes of legal analysis I learned in law school before graduating 15 years ago are now obsolete, and the precedents they generated overruled. So, things can change quickly. Indeed, one history of human progress is mostly one of small handfuls of people suggesting the present consensus reality is wrong about something important, surviving ridicule and scorn, and ultimately, seemingly against all odds, eventually prevailing. I’ve seen such shifts in my own work on the micro- and macro levels. So, with deep gratitude and inspiration from Christopher Lasch, here goes.

ICE’s Current Detainers Regime is Categorically Illegal

ICE detainers are the primary means by which the agency carries out domestic (interior) detention. A person has contact with state or local (non-ICE) cops, becomes subject to an arrest, and sometimes, a criminal charge, and then, through fingerprinting and databases and a healthy dose of racial profiling, ICE sends the person’s jailor or custodian a notice that the agency wants to detain the person. This notice, a “detainer” - is a request. Most jurisdictions around the country honor them — which, as courts have concluded, is itself usually an unlawful detention and false imprisonment, but I digress. Some states even passed laws requiring local jails to hold people ICE wants to imprison based on these detainer request notices.

Unless you’re a U.S. Citizen and can prove it immediately, as was the case in Leon County, Florida yesterday, you’re essentially at the mercy of the federal immigration bureaucracy once you’re in state or local custody on a detainer. By most accounts, around 80-90% of ICE apprehensions in the interior occur through detainers. It’s not the high-profile raids, or the courthouse tackles, or the shattered car windows that fill ICE detention centers and keep the vans moving from jail to jail. It’s detainers.

Every great mentor I’ve ever had, and ever great lawyer I’ve ever been privileged to practice with, has followed a simple pattern when confronting manifest injustice cloaked in legality: Start with the legal authority the unjust actors might cite to justify their actions. If those justifications are illegitimate, because they’re claiming more power than they have, dig in and push, so that you cut off every conceivably pathway to using that power until the injustice ends. It doesn’t always work. But it nearly always disrupts the status quo in ways that are beneficial to organized communities.

A Very Basic Review of Constitutional First Principles

Executive-branch agencies are creatures of statute. They have limited, enumerated powers, defined by Congress. They may also enjoin discretion in how they carry out their Congressionally assigned tasks. But that discretion does not extend beyond the limits Congress set in granting them their authority. This, too the right, is canon. It’s the basis of the modern attacks on the regulatory state, and a key reason the Supreme Court overturned Chevron, among many other precedents. Under this system, a regulation cannot sweep broader than the Congressional power conferred upon the regulator who’s promulgating it. If it’s Congress’s job to do, only Congress can do it. And if there’s a gap to be filled, bureaucrats can only fill it within the powers they enjoy as a result of their enabling statute, among other important constitutional constraints.

We need to acknowledge another basic principle in understanding the language of Congress’s conferral of power onto the bureaucracy before we explain why most ICE detainers are unlawful. This principle boils down to four important canons of statutory construction. First, expressio unius est exclusio alterius. If a statute says one thing, it implies that other things are intentionally left out. If I make a law saying there will be a 10% tariff on bananas, oranges, and pineapples, that law implicitly excludes blueberries, grapes, and cherries. Second, we read statutes to give every word its plain meaning and effect. We will not torture the ordinary meaning of words to achieve at a predetermined outcome, or to avoid one we think might not be a natural, intended consequence of the drafters. Third, and as a corollary to the first two, we avoid readings of laws that render parts of them “mere surplusage”. That is, we give effect to all the words in the statute, and ignore none of them. Fourth, and related to each canon that’s come before, when there is a general provision conferring broad power, and a specific provision that defines how a certain part of that power may be exercised, the specific provision controls. To reach the opposite conclusion would be to violate the first three principles.

Our final piece of the analytical puzzle requires us to understand the implications of the fact that Congress grants the Executive Branch and its agencies enumerated powers (in part because only one member of the Executive is elected, and in part because the structure of checks and balances requires this). Where an agency claims more power for itself than Congress granted it, for example, in a regulation, that regulation is ultra vires, literally, “beyond one’s power or authority”, and consequently, void ab initio, which is to say, invalid from the beginning.

To summarize/simplify: Congress makes laws. The words it uses have meaning. Executive agencies are bound to enforce those laws. Every word of them. No less. No more. This is the structure of our system. At least on paper.

Why ICE’s Current Detainer Regime Is Illegal Under these Principles

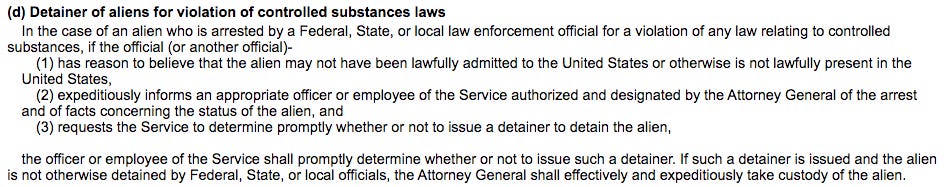

What is the statutory authority Congress granted ICE to issue detainers? We find it first in 8 U.S.C. 1357(d), or Section 287(d) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA):

Notice the discretion built into the statute. But this is not the only, or even the primary authority ICE cites when it goes to court to defend detainers. Instead, it cites the general powers of the Secretary of Homeland Security (previously the Attorney General) to enforce immigration laws, 8 U.S.C. 1103(a)(3), and a regulation DHS promulgated governing the agency’s detainer regime: 8 C.F.R. 287.7.

Start with the powers of the Secretary: “[Sh]e shall establish such regulations, prescribe such forms of bond, reports, entries, and other papers; issue such instructions; and perform such other acts as [s]he deems necessary for carrying out [her] authority under the provisions of this chapter.”

Pretty broad, right? So then, the Secretary will defend detainers by citing to this power to “establish such regulations . . . as [she] deems necessary for carrying out [her authority].” When it comes to detainers, those “regulations” are found at 8 C.F.R. 287.7(d):

While the regulation itself includes in its title a reference to INA 287(d)(3) — which only confers power to issue detainers for controlled substance offenses — its text ropes in two more statutory authorities — Section 236 of the INA, and “this chapter 1”. Section 236 of the INA, 8 USC 1226, deals with the apprehension and detention of “aliens” (the legal term U.S. law uses for humans unfortunate enough to have been born outside its territory). The specific provision that confers the power on the Secretary to issue detainers is INA 236(d):

To carry out this duty, the Sectary must first determine if the person who might be subject to the detainer is described in paragraph 1(E) of INA 236. That paragraph says:

Under paragraph 1(E), the person against whom the Secretary issues the detainer must be someone who is (i) inadmissible under one of the four listed grounds; AND (ii) charged with, arrested for, convicted of, or admits to one of seven listed crimes: (1) burglary, (2) theft, (3) larceny, (4) shoplifting, (5) assault of a law enforcement officer, or any crime that results in (6) death or (7) serious bodily injury to another person."

Putting these two statutes together (INA 287(d) and INA 236(d)), we can add controlled substances to the list of offenses for which Congress authorized DHS to issue a detainer. Looking back to the implementing regulation that creates the power to send a detainer request, we see no corresponding limitation on the power of designated immigration officers to lodge these detainers:

DHS’s detainer regulation thus excludes the statutorily-defined limits on the Secretary’s authority to issue detainers. And because it does, ICE sends detainer requests for people arrested for all manner of petty offenses, ranging from driving without a license to trespassing, and points in between, without satisfying the requirements laid out in the statute. In this regulation, unlike the outcome in Bostock, we have more law than the written word contemplates.

Surely Smart Immigration Litigators Have Challenged This Gap in Legality, Right?

Right. In Committee for Immigrant Rights of Sonoma County v. County of Sonoma, 644 F. Supp. 2d 1177 (N.D. Cal. 2009), the ACLU of Northern California, representing a putative class of immigrants and immigrants’ rights organizations, brought an Administrative Procedure Act (APA) claim alleging ICE’s issuance of detainers for people not described in the statute. It didn’t work. The Court applied Chevron defense and concluded the agency’s reading of an inherent authority to issue detainers, indicated by the broad language of 1103(a)(3), was reasonable, and deferred to this reading.

Chevron is dead, and with it, courts’ power to defer to loose statutory interpretation untethered to the language Congress passed to constrain and enable the agency.

There is no inherent authority to issue detainers. In fact, as the late, Great Prof. Chris Lasch astutely observed, Arizona v. United States shows why detainers in their current form are unconstitutional, and the entire system is ultra vires.

As detainer litigation warriors Mark Fleming at NIJC alongside an army of partners and extremely brave noncitizens in courtrooms across the the U.S. have established, detainers themselves very often violate the Constitution. They lead to unlawful arrests without probable cause, over-detention of people who are entitled to their freedom, and illegal commandeering of state and local resources to carry out federal enforcement schemes of dubious legality.

So, What is to be done?

Sue to Enjoin ICE from Issuing Any Detainers. ICE could and should be enjoined tomorrow from issuing a single detainer request based on 8 C.F.R. 287.7(d). Without Chevron to pick up the slack in the agency’s shoddy statutory construction, the regulation is invalid and ultra vires, and there is no lawful system under which the feds can conceivably issue any detainer. The harms this system are causing to people in communities and local governments are overwhelming, immediate, and irreparable. Local officials are forced to divert resources and face liability because the federal government has spent two decades lying to itself and the public about this troublesome authority. The most powerful litigant to challenge the detainer system, which is to say, the present architecture supporting 80% of ICE arrests in the U.S., would a be a state or local government forced to choose between being labeled an unlawful “sanctuary” jurisdiction for refusing to bow to this unlawful federal kidnapping scheme. But U.S. citizens and people currently in custody subject to illegal detainers would be vital components of the fight as well.

Halt Compliance with Unlawful Mandates. If you’re a state or local policymaker with authority over a jailor in receipt an ICE detainer request, it’s incumbent upon you to educate yourself and your colleagues about the legal infirmities of the ICE detainer scheme. If you’re working in a jurisdiction that’s been mandated by a state to enter into a 287(g) agreement with ICE — particularly a Jail Model designation where your officers are going to be lodging detainers or facilitating detentions based on them in local jails — understand that you’re being asked to support a practice that is, by any reasonable interpretation, not lawful. Obeying the law means halting the issuance of and compliance with ICE detainers, and going to court to defend that decision, if necessary.

Denaturalize the Bureaucrat-Driven Violence of Imprisonment by Fiat and Labor Extraction by Force. In his seminal article, Rendition Resistance, the late Professor Lasch connects modern immigration detainers with the long history of rendition resistance to fugitive slave laws, and the legal mechanisms slavers used to enforce them.

At the end this article, published a year before Menocal v. The GEO Group, Inc., the nation’s first case challenging forced labor practices of ICE’s detention contractors was filed in his home state, Prof. Lasch invites us to understand the system’s motivations behind slave rendition as historical antecedents to the present system’s motivations driving ICE detainer practices.

ICE’s largest detention contractor is currently subject to three putative or certified class actions alleging forced labor practices and deprivation schemes enable their detention centers to operate at a profit. ICE’s second largest detention contractor is subject to a certified, nationwide forced labor class action that’s survived preliminary challenge at the Supreme Court. The Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), as amended by the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA), acknowledged a gaping hole in U.S. law, exemplified by the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Kozminski, that allowed modern slavery to proliferate within a system that nearly abolished it. Congress fixed this gap with the TVPA. Detained immigrant workers are using its private right of action to uplift the truth of what goes on in ICE custody, and seek redress. The modern legal context of “Rendition Resistance” is more pressing than ever, because the modern expansion of carceral migrant enslavement is going into hyperdrive. It’s long past time we listen to Lasch, and halt ICE’s illegal detainers regime for good.