A Bump on a Log

ICE’s wholesale noncompliance with FOIA’s Affirmative Disclosure Provisions lands agency in court.

A FOIA request about FOIA requests

Al Otro Lado’s #DetentionKills Transparency Initiative and co-counsel sued ICE in late May of this year under the Freedom of Information Act. Like most FOIA suits you’re probably familiar with, this one involves a request under 5 USC 552(a)(3). This part of the Act allows requestors to demand agency records. The request we made pursuant to 5 USC 552(a)(3)—a request to see ICE’s FOIA logs—is something we wouldn’t have had to make before 2018. That’s because ICE used to affirmatively post an imperfect version of its FOIA logs until then.

But unlike CBP, DHS, and DHS-OIG, and in contravention of best practices recommendations from the federal government’s FOIA advisors, ICE doesn’t post its FOIA logs. Not anymore, anyway. It stopped doing so without explanation.

As alleged in AOL’s complaint, FOIA logs are an essential tool savvy requestors can use to determine what’s already been sought and obtained by the public. Using this tool allows all requestors to better formulate requests.

As elaborated on in the original complaint, posting FOIA logs benefits the public and the FOIA office in a variety of ways. It enhances transparency. It increases efficiency. It ensures consistent adjudication and disclosure. And it allows those of us in the public to have the necessary knowledge and data to make the government’s job more manageable.

To be clear, ICE, like all competent FOIA offices, creates these logs anyway. They have to. FOIA requires the agency to assign individualized tracking numbers to all requests that will take more than 10 days to process. We assume ICE does that sequentially (imagine the ticket at the deli counter), rather than randomly (imagine the lottery drawing with numbered ping pong balls inside the rotating cage). FOIA requires the agency to determine an estimated date of production. We assume ICE FOIA does that by looking at how many requests are ahead of the one whose production date they’re estimating, rather than using numerology or divination. FOIA and DHS’s implementing FOIA regulations envision multi-track request processing — simple and complex. We assume ICE generally works on requests in each track using a first-in-first-out logic, rather than a grab bag or fishbowl full of tiny plastic prizes method. And finally, if ICE wants more time in litigation to complete its search for and review of responsive records, it’s got to show exceptional circumstances (which don’t include a predictable agency workload) AND due diligence as to the request at issue. We assume ICE doesn’t think due diligence means throwing all the FOIAs it gets down some stairs and randomly starting with the request that lands face-up.

And ICE’s FOIA trainings back up these assumptions, at least so far as we can tell.

So we requested ICE’s FOIA Logs in October of 2021 and waited. And waited. And waited.

In January 2023, a federal judge in Los Angeles declared in another AOL-led FOIA suit, Owen v. ICE: “It should not take a lawsuit for an agency to comply with FOIA.” ICE — the agency against which the court entered declaratory judgment — apparently missed that memo.

A FOIA suit about preventing FOIA suits.

As fun as the idea of FOIA lawsuits might be for requestors in the abstract, the reality of suing ICE and DHS FOIA agencies in federal court is often painful, slow, and demeaning. That’s by design.

We learned this week in response to an August 2020 request that DHS FOIA professional Bradley E. White apparently instructed DHS FOIA officials in 2019 to delay or slow production FOIA suits if compliance would “strain” their office. Telling agency FOIA officials to “push back” on AUSAs where production schedules in litigation would put a strain on the agency FOIA office is certainly one approach to reading the statute. Unfortunately for the requesting public, DHS FOIA’s White doesn’t actually apply any limiting principle to this advice. It’s unmoored from the plain language of the FOIA statute, and leaves no real yardstick by which to measure strain. Like, of course you didn’t want to be sued. Of course you’re being forced to do something. That’s because you didn’t do it before you got sued. That’s the point of the lawsuit. Telling the Department of Justice you still won’t do the thing you got sued for not doing because it’s inconvenient without even attempting to connect that “push back” to any legal standard is the sort of thinking that gets you sued in the first place.

We think DHS and courts would agree with us when we say there should be fewer FOIA suits and more affirmative releases. We see the problem as particularly urgent at ICE, where FOIA compliance basically fallen off a cliff, according to DHS’s own Chief Privacy Officer’s report:

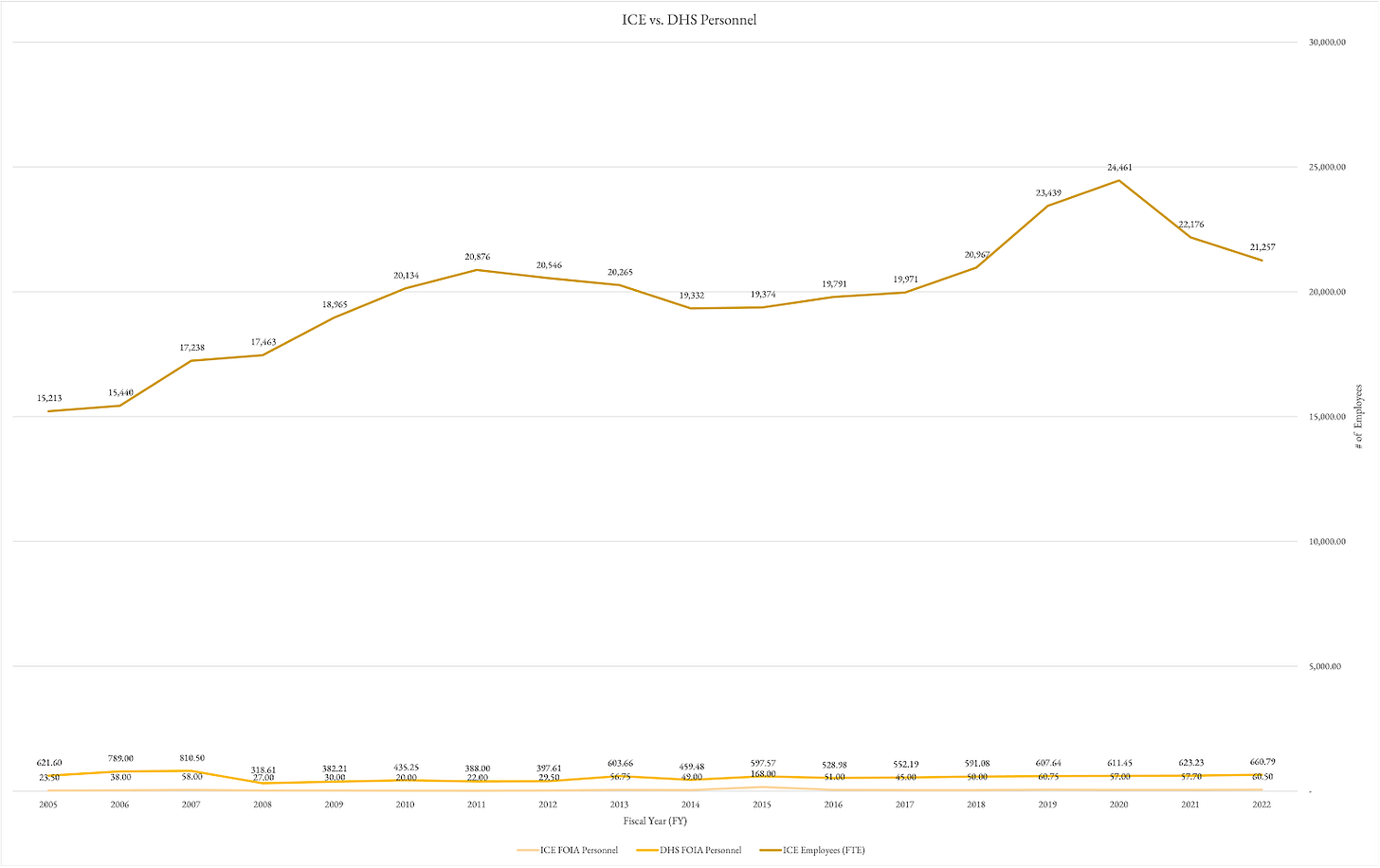

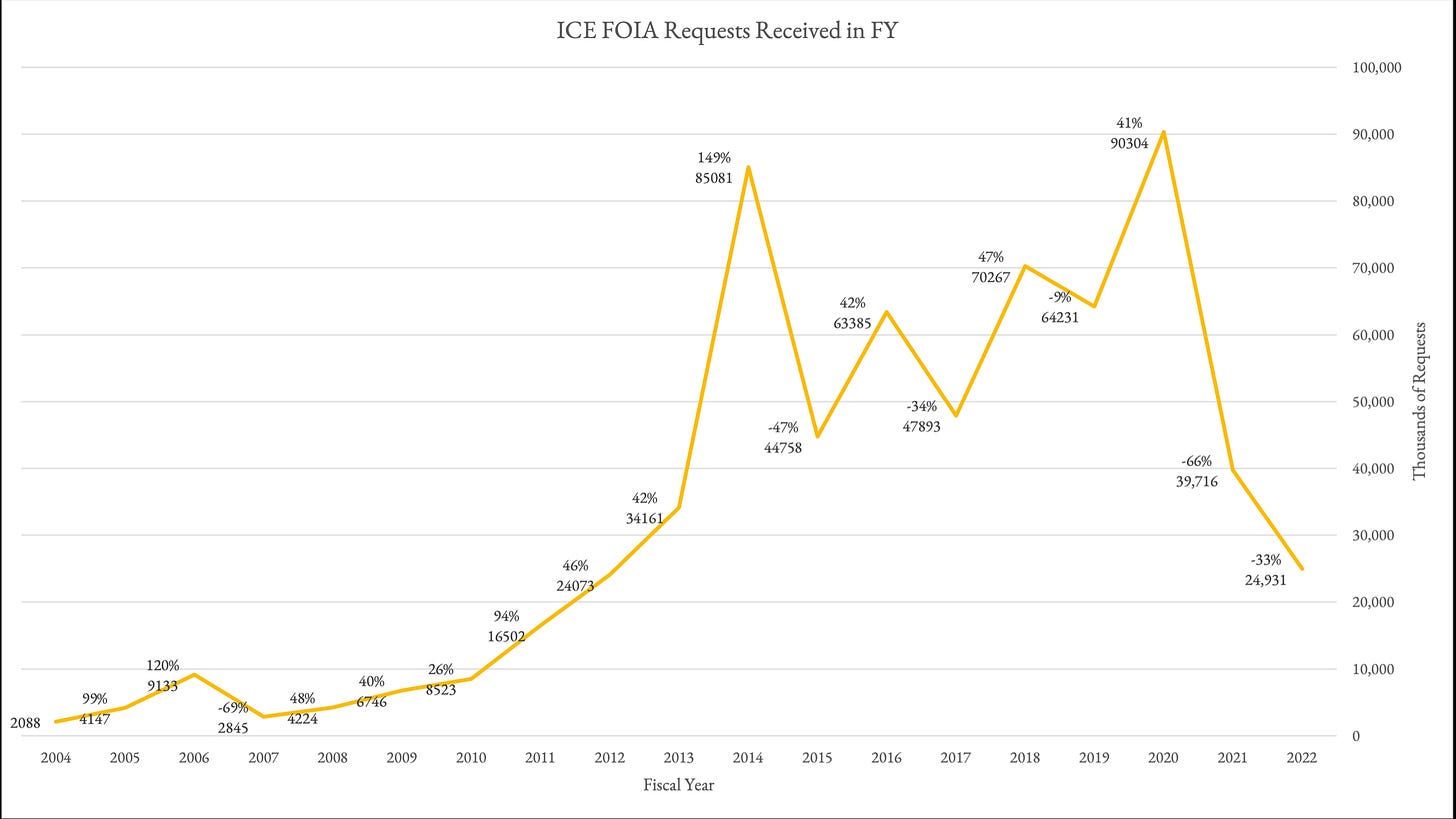

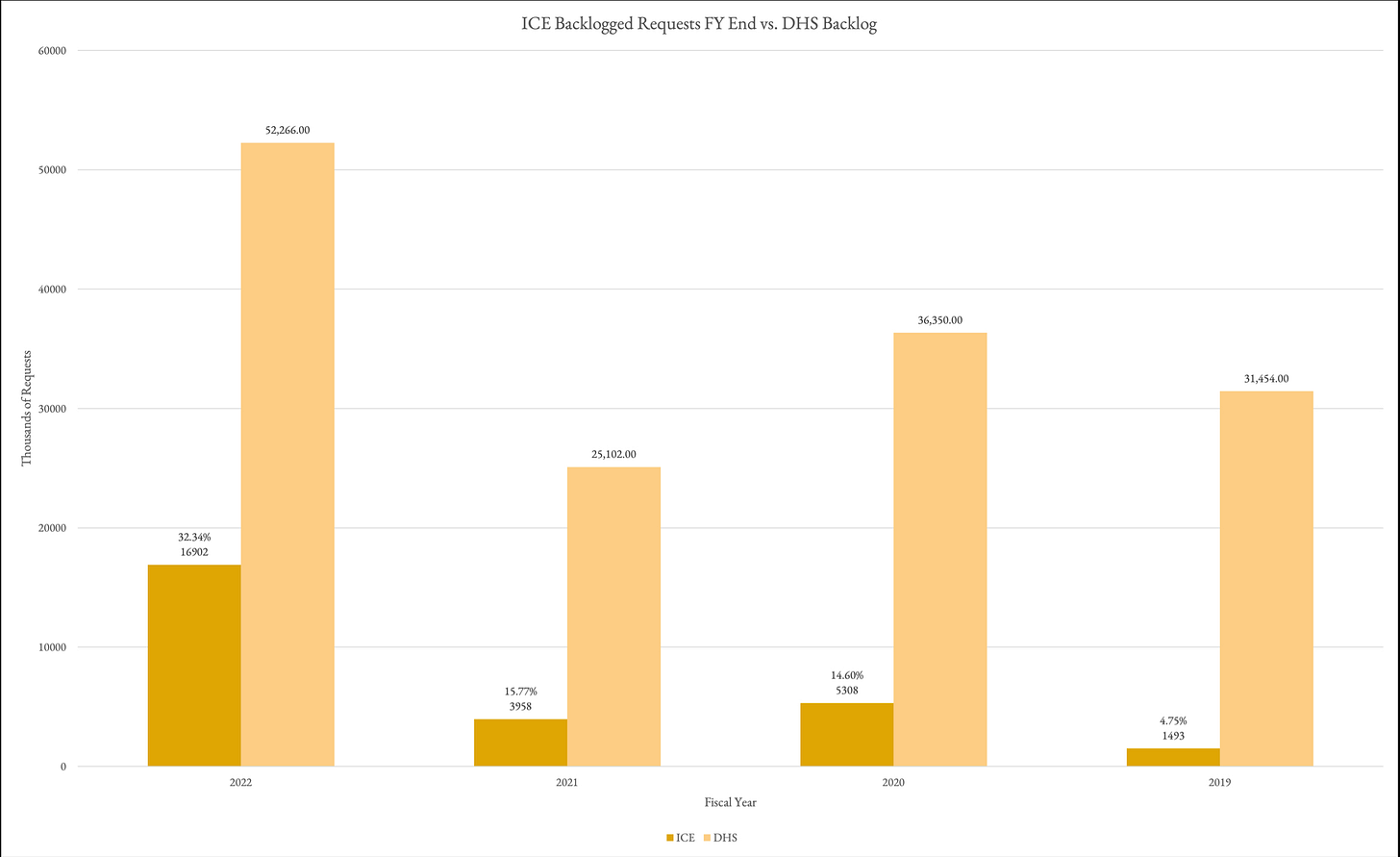

Northwestern student and Buffett Institute Deportation Research Clinic affiliate Kendall McKay put together the following visualizations of our ICE on Fire post.

DHS / ICE FOIA personnel have not increased at anywhere near the rate of the staffing increases we’ve seen in the agency. The idea that you’re going to hire thousands more people without creating tons more records that might be FOIA’d is folly. But that’s what ICE did:

The idea that you get to “push back” on AUSAs after running a FOIA office that’s demonstrably less efficient is folly:

The idea that you should be able to interminably delay FOIA productions in litigation on the basis of representations about how overworked your FOIA office is, and that you’d reflexively invoke the unusual/exceptional circumstances provision of FOIA despite the fact that you actually got fewer requests is folly:

The idea that you’d tell a Court and your own professionals that you can simply extend the time to produce FOIA records after a lawsuit because you’re working to clear your backlog and exercising due diligence when responding to EVERY FOIA request is belied by ICE’s own FOIA data:

The idea that you’d waltz into court expecting to benefit from a presumption of regularity in your FOIA operations when you’re processing FOIA requests at a slower rate than you have in 10 years is folly:

The idea that you’re entitled to a presumption of good faith and reliability in your declarations when you’re admitting to violating one part of the FOIA statute as much as 87% of the team is folly:

We’d like to not have to litigate FOIA requests against ICE anymore because ICE engages in serial half-truths and deleterious litigation tactics, like its totally made-up 500 page-per-month processing rate, that make litigation more costly and time-consuming that most advocates, organizers, and community members can afford.

If more information about what’s been requested and released were public, we wouldn’t have to spend so much time making requests and trying to get things re-released. There would be more information about government corruption and abuse, more transparency, more democracy.

Who’s against that? Who thinks that’s not worth paying for?

DHS’s Congressional Budget Justifications for the FOIA office and the annual ICE FOIA budget supplies the answer.

[(a)(2)], Brute?

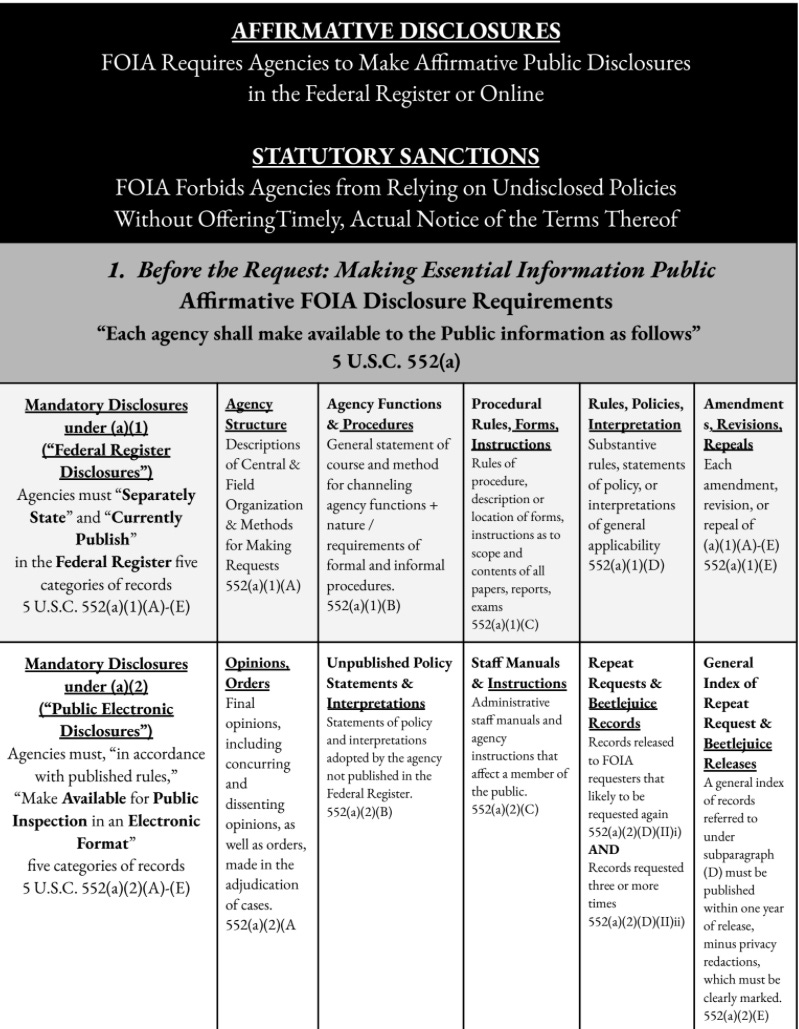

Our original complaint also sought something else — something that, if we get it, will mean we shouldn’t ever have to sue ICE for the same type of records again. Specifically, we sought an order requiring ICE to comply with the part of FOIA aimed to avoid lawsuits for records like this one.

Last year, Claudia Valenzuela, Raul Pinto, and Emily Creighton showed us a path forward from FOIA fatalism to FOIA maximalism, at least in the immigration arena. That path is the plain language of FOIA itself. Rather than giving in to despair and biding our time through rolling productions in litigation after litigation, Claudia & the gang encouraged us to read the law and reconsider what it entitles the public to BEFORE we file a request for documents.

What we found when we read FOIA’s affirmative disclosure provisions is that a TON of the stuff we’ve been requesting for more than a decade—policies, procedures, guidelines, manuals, stuff released to other requestors—is stuff the agency is already supposed to be disclosing without the need for any request under (a)(3).

If you’re a frequent DHS FOIA requestor, I’ll bet you, like me, have previously requested something from ICE or a DHS agency component that should have already been disclosed:

If you’re the government FOIA officer, and you’re getting a ton of requests for stuff you were already supposed to publish online in your FOIA reading room, and index in your FOIA log so that the public can find it before a even having to make a request, and you’re demonstrably not living up to those obligations, it seems like you’d have a hard time demonstrating due diligence, regularity, reliability, or good faith in any (a)(3) litigation. You’re in serial, unabated violation of the most basic disclosure obligations you’ve undertaken as a FOIA officer. Are courts really supposed to care about the “strain” FOIA suits filed because you didn’t make the (a)(2) affirmative disclosures that triggered you were supposed to, creating the need for requestors to file (a)(3) requests and then sue you when you ignore them for 2 years? Really?

“The fault, dear Brutus, in not in our stars, but in ourselves.”

FOIA Logs or Everything

With this underlying logic informing AOL DKTI’s original complaint, we sought an agreed order from ICE to begin posting FOIA logs online. ICE, through the DOJ, confirmed shortly after being served that it had the logs, and was going to see how long it would take to start producing them. Nobody could explain why they stopped getting posted affirmatively on the agency’s website.

ICE has thus far refused AOL DKTI’s invitation that it enter an agreed order to restart posting FOIA logs online.

So, in July 2023, we amended our complaint. This time, we attached a printout of ICE’s FOIA reading room. The amended complaint documents a host of areas in which ICE appears to be in flagrant violation of its (a)(2) affirmative disclosure obligations. We seek relief in the form of a wholesale release of these records to #DetentionKills Transparency Initiative, which will then post them online, unless ICE chooses to post them itself.

Funny thing about not posting this stuff, though. It’s a thing ICE might consider when daring AOL to seek an order that the agency has violated (a)(2) by failing to affirmatively disclose this record or that. Congress took affirmative disclosure of agency policies, practices, guidelines, manuals, and instructions affecting a member of the public so seriously that it included a sanction for keeping these things secret.

Specifically, an agency’s failure to affirmatively disclose and index a required policy record, combined with its failure to give timely, actual notice of the terms of that record as applied to a member of the public, e.g., a policy, means the agency cannot enforce that policy against that member of the public.